‘Imvo Zabantsundu’ 140 years later: ‘To see us as we see ourselves’

The launch of this newspaper set firm the roots of black journalism in South Africa. This also marked a break from the missionary-controlled newspapers that, from time to time, tended to censor the views of Africans which went against the grain of missionary and colonial ideology.

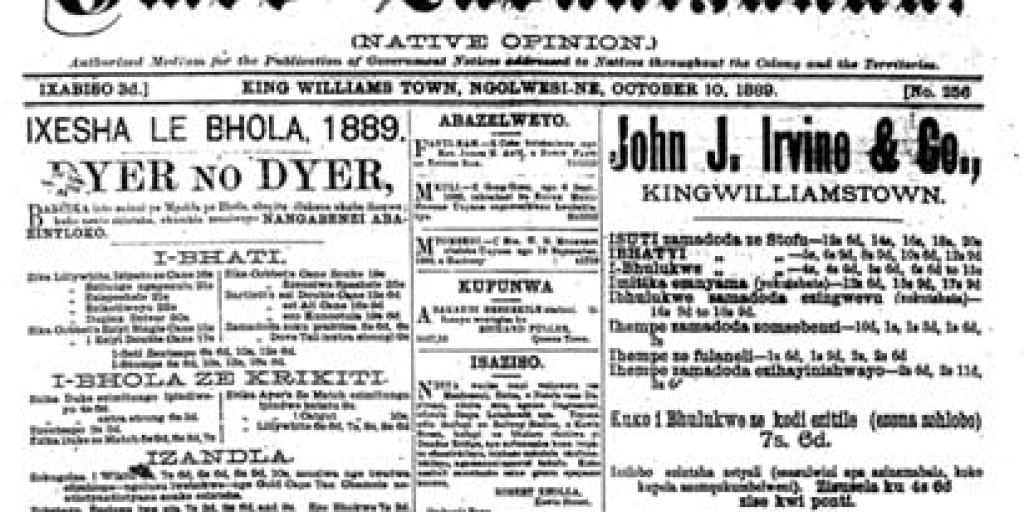

As the name of the newspaper – Imvo Zabantsundu – suggests, the thoughts, aspirations, opinions of those whose skins look like the soil, and the voices that were to be foregrounded in it were unapologetically African.

As a young democratic dispensation that is still grappling with the issues of identity and representation, what can we learn from the legacy of this newspaper? As a country still in the wake of the apartheid regime that censored the voices that shouted for a total liberation of black tongues and beings, what lessons can we draw from Imvo?

As we look at Imvo’s legacy, it is important to note that this newspaper was launched into a culture of periodicals that had been established in the Eastern Cape since the early 1830s. These publications are typically referred to as the ‘Early South African Black Press’. The difference this time around is that it was the first time the actual ownership and control were in the hands of an African.

Before launching his publication, Jabavu was the editor of Isigidimi samaXosa (1870–1888) which had more African editors than missionaries. Some of its editors included Elijah Makiwane, John Knox Bokwe, Jabavu and William Wellington Gqoba. The forerunner to Isigidimi was Indaba, which was edited by Tiyo Soga.

All these African writers, journalists and editors occupy a very special place in the history of South African intellectual life and culture. Although still marginalised, their intellectual oeuvre is a reference point for many of the debates inside and outside of the academy, especially in disciplines such as history, journalism, media studies and African languages and literature

The importance of engagement in this work outside the ivory tower of institutions is important, especially because this work was lived and circulated outside of the academy which was historically reserved only for white people. The late Professor Bhekizizwe Peterson called this ‘Black public humanities’.

Marking the departure from moderate newspapers such as Isigidimi and colonial press like the Grahamstown Journal, Jabavu wrote in the first issue of Imvo on 3 November 1884: ‘Although the columns of the colonial press have ever been open to any native to unbosom himself, still, speaking as natives who have had opportunities of observing the newspapers in the colony, we have concluded not dissimilar to that expressed by our talented friend, the Rev E. Makiwane … that, in addressing Europeans, our countrymen felt, rightly or wrongly, that they spoke or wrote “out of courtesy”.’

He continued: ‘Students of the native question, then, will rejoice at living to see a regular organ of native opinion set up.’

‘In that organ they will, no doubt, not only expect “to see themselves as others see them”, but also to see us as we see ourselves.’

Jabavu’s inaugural column in Imvo addresses the power of ownership and what that does in freeing or freezing tongues. As Jabavu puts it, to be included in terms that make it hard to freely express oneself is equal to self-censorship. For Jabavu, Africans were not expressing themselves as freely as they could in the press afforded by colonial and missionary enterprises.

This underscores the power of representation and the importance of having a platform where the raw views and opinions of Africans were to flourish. This is especially the case in the space where black people were thinking about what it meant to be an African citizen under British imperialism.

They were also thinking about the complexities of that in a changing South Africa. The political elite and activists responded with much enthusiasm in contributing to the paper on various issues affecting Africans – from sports, parliamentary issues and education matters to social commentary.

African intellectual and political historian, Professor Andre Odendaal, writes in his book, The Founders, that Imvo enabled Africans to express their point of view for the first time and exposed missionary interests as divergent from those of Africans in a way Indaba, Isigidimi and other newspapers could never have done.

At the heart of the foundation of black journalism, we learn that the tongues of the marginalised were critical in determining the political, cultural and social discourse. Although Imvo had an English section, the most dominating language was isiXhosa, in a similar way that isiZulu and Setswana dominated in sister newspapers such as Ilanga lase Natal and Sol Plaatje’s Koranta ea Becoana.

In other words, African languages enjoyed finding expression in public intellectual and political life in the making and unmaking of South Africa.

If we were to count the number of publications in indigenous languages that are well funded and with high-quality standards in South Africa today, compared with those that are only in English, we would bury our heads in shame. The continued English hegemony at the expense of indigenous languages is one of the failures of the new democratic dispensation and the media landscape should deeply reflect on this

Imvo was criticised by some sections for its financial support from the Cape liberals, such as Richard Rose Innes and James Weir. With the funding coming from its liberal white friends, the paper was confronted with the need for compromise through alliances with white politicians and sympathisers.

The interests of these politicians and sympathisers were not always aligned with those of African people and this challenge continued to confront Imvo until its demise.

Although we saw the flourishing of many newspapers, such as Izwi Labantu, published in African languages, the decline in funding, the African ownership and control of newspapers during the dark days of apartheid signalled a huge shift in black journalism.

The suppression of black voices in the media, evident in the decline of African-owned and controlled publications, reached its zenith during the apartheid era.

Black Wednesday, a dark day in South African media, was one of the starkest manifestations of this. The day – 19 October 1977 – saw the banning and closure of several publications that served as a voice for the marginalised.

These included The World and Weekend World, then the prominent voices against apartheid. On the same fateful day, several journalists, including Percy Qoboza, the editor of The World, were detained without trial.

The regime also introduced stricter censorship laws, further limiting the freedom of expression and the press.

It is a legacy that reminds us of the ongoing need to safeguard media freedom and fight for a more just and equitable society.

As we mark the 140th anniversary of Imvo Zabantsundu, we should ponder on the complexities around representation and ownership of media in South Africa today.

How many media entities are owned by black people? How many of the print and other media champion the views, opinions, aspirations and exasperations of black people? Is our democracy stronger when African languages continue to be marginalised in the public space?

Jabavu, with all his complexities, started a newspaper whose primary aim was to champion the aspirations of Africans. In what ways do we draw on this legacy?

What platforms are we setting to paint the dreams and aspirations of black people on the canvas of meaningful emancipation and self-determination?

- This article was first published here

- KaNtshingana is a lecturer in the School of Languages and Literatures (African languages section) at the University of Cape Town. Nkoala is an associate professor in the University of the Western Cape’s linguistics department, and a Public Representative on the Press Council