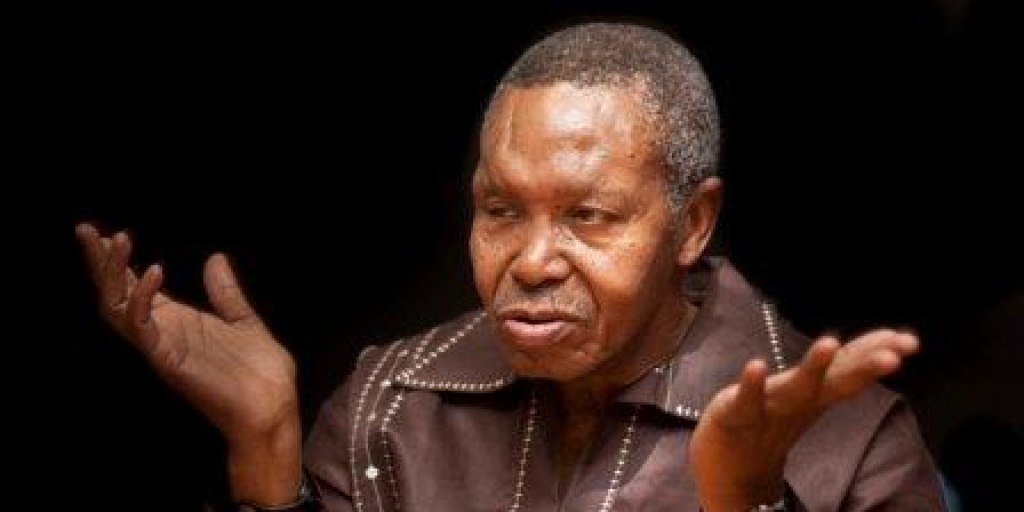

Rhodes University’s Faculty of Commerce honours Joe Thloloe

Chancellor Professor Gerwel, Vice-Chancellor Dr Badat, Members of the Board of Governors, Senate, Council, Deans, Professors, Lecturers, graduands, relatives and friends of the graduands.

It is truly a privilege to stand here and receive a doctorate from Rhodes University.

I have had a long relationship with the Rhodes School of Journalism and Media Studies and have been in and out of its offices and lecture halls for years. In various capacities, I have employed graduates from here. And among my friends in that department, I’m proud to count people like Anthea Garman, Lynette Steenveld, Chris Kabwato, Jane Duncan, Francis Mdlongwa, Reg Rumney, Robert Brand and Guy Berger.

Guy has made the school shine among the world’s best journalism training institutions. I was a witness as Guy left the newsroom at the alternative newspaper, South, and joined academia. I was a witness as he systematically entrenched the credibility of the school and I saw him as he knocked at doors, soliciting support for a Media Matrix.

Some of us thought he was too ambitious, but the twinkle in his eye did not diminish. That twinkle is now an impressive structure of brick and mortar, a real monument to Guy.

He will of course be coy about it, say it is not quite what he had in mind. He will talk about the team effort that went into creating the Matrix. I, for one, salute him for his incredible leadership and his contribution to African and world journalism.

Ladies and gentlemen, in the 50 years I’ve been in journalism, I never for a second dreamt that I would be honoured by a university. If I had, I would not have expected it to come through the Faculty of Commerce here at Rhodes. The business that I know intimately is the business of journalism, which some people might believe is far from ‘commerce’.

Ladies and gentlemen, I’m grateful to my friends Dr Thami Mazwai and Ambassador Dumisani Kumalo, my sister Sibongile Mafata and my children Nokuthula, Moroesi and Mangaliso and to my partner, Diana Claaste, for being here with me today to be witnesses on behalf of the thousands of people that I can see in my mind’s eye, people applauding their handiwork, people who shaped who I am today.

Leading the people I see in my mind are my 92-year-old mother Nokuthula, who is still in Orlando East, Soweto, in the house where I was born, and my late dad, Joel Letebele Thloloe.

I see my teachers at Law Palmer Primary School and Orlando High School. Some of them, like Ellen Kuzwayo and Tamsanqa Kambule, became national heroes; while others, who did not make it into the history books, will live on in the pupils they taught with such passion.

I see the founding president of the PAC, Mangaliso Sobukwe – a true revolutionary who had the integrity and the humility to match his deeds to his words. He shaped my values in society.

I see Matthew Nkoane, who gave me my first lessons in journalism in 1960 as we sat on sisal mats, which were also our beds at night, and scribbled with pencil stubs on toilet paper in the cells at the Stoneyard Prison in Boksburg and at the Stofberg Prison in the Northern Free State. Ironically Stofberg had previously been a teacher training college.

I see Boy Gumede and Doc Bikitsha, who in 1961 took me to my first job interview at the-then Bantu World and also introduced me to real-life journalism and the hard world of brandy and jazz.

There are literally thousands of these family and friends who chipped away to bring out this person who stand in front of you. Can Themba, Stanley Motjuwadi, Casey Motsisi, Aggrey Klaaste, Lesley Sehume, Alf Kumalo, Juby Mayet, Mike Mzileni, Mike Norton, Mabu Nkadimeng, Percy Qoboza, Dave Hazelhurst, Jon Qwelane, Frank Ngidi, Zwelakhe Sisulu, Mathatha Tsedu, Bill Manning, Dr Tony Earls and his wife Dr Maya Carlson, Howard Simons, Philip Selwyn-Smith, Quraysh Patel, Vas Soni, Aggripa Tshabalala, Phil Mtimkulu, Kanthan Pillay, Tim Knight, Dr Nthato Motlana, Khotso Seatlholo …

I see them applauding their work, even though some are frowning a little and saying: ‘Oh, we should have cut a little deeper there and, eh, smoothed out a bit more over there … ‘ I hear another replying: ‘Yes, it isn’t perfect but that’s what makes it so interesting, so human’

Sitting glumly among them are those who also contributed unintentionally to this shape – people like the security policemen who tortured me in lonely offices haunted by screams when I was detained under Section 6 of the Terrorism Act or under the Internal Security Act.

I’m pretty certain that each one of you graduands can also see the people who pushed and nagged you until you reached this high point in your life.

Ladies and gentlemen, this honour comes exactly 50 years since I started out in the business of journalism. It also comes at a time when press self-regulation in our country has come under intense scrutiny.

Today’s culture has created artificial boundaries and specialisations. For example, today I’ve come to accept that I know nothing about commerce and leave discussions about it to the economists. Truth is that every day I do buy and sell goods and services and I have to budget for my bond and my children’s university fees. I am at the centre of the world of business.

In the same way, my fellow graduands here have probably been made to think of everything except the practice and ethics of journalism, and yet they are at the centre of the journalism project in the same way that every citizen is. Perhaps even more than that – you might end up owning or managing a media enterprise.

Ladies and gentlemen, in the 68 years I’ve been alive and the 50 years in journalism, I have seen the worst and best that our country is capable of achieving. This before and after the collapse of apartheid. I have seen the best and the worst from business and commerce. And I have also seen the worst and the best that our journalism can achieve.

The year before I started out as a journalist, South Africa showed off a little of the horror of apartheid to an international community that until then had been too happy to give South African whites the benefit of the doubt: the police gunned down 69 people and injured scores of other unarmed people in Sharpeville in Vereeniging. Journalists broadcast the pictures and the text from the blood-soaked dust of this Vaal township.

Many of us had been arrested at the Orlando Police Station on Sharpeville Day and had heard that our comrades had been massacred, but the enormity of the event didn’t hit us fully until we opened the newspapers in our cells on March 22. I read the stories through my tears.

That massacre was a crucial turning point in our history.

As the world changed in front of us, there were journalists and publications that supported the killers. For them apartheid was just. As a person who has always fought for freedom of expression, I should concede that they had the right to hold their views, even when those were as pernicious as they were

My concession is tempered by the fact that people who held opposing views were forbidden from expressing them. Ultimately, it was not that the views the supporters of apartheid held were obnoxious, it was the translation of those views into acts that dehumanised and butchered other South Africans that appalled the whole world.

I joined the Bantu World [and] it was a few years later that the adjective was dropped and the newspaper became the World, and my eyes were opened to the world of journalism of the time, a miniature of the apartheid world outside.

I will not go into the story of journalism under apartheid: it has been well documented. The cowardice of many journalists and the courage of hundreds of others who were imprisoned, banned, placed under house arrest, exiled or even killed during that time are on record.

I will leap to April 27, 1994. On that day as we snaked into voting stations and made our crosses on ballot papers, those of us who had opposed apartheid were finally vindicated. For me however the real victory was to come two years later when I saw the 1996 Constitution, with its guarantee of freedom of expression and freedom of the press and other media.

Section 16 of the Constitution enshrines the right to freedom of expression as follows:

(1) Everyone has the right to freedom of expression, which includes:

(a) Freedom of the press and other media

(b) Freedom to receive or impart information or ideas

(c) Freedom of artistic creativity, and

(d) Academic freedom and freedom of scientific research

Interesting wording this … which includes, our press freedom, our freedom to receive and impart information and ideas, freedom of artistic creativity, academic freedom and freedom of scientific research … are parts of everyone’s freedom of expression.

Any person is free to scribble on a piece of paper, photocopy his or her scribbles and distribute them. Any person can stand on a soapbox and shout her views to whoever is prepared to listen. Any person is free to express his choice for ward councillor in the coming local elections. Freedom of expression is the cornerstone of democracy.

Our society has been very generous to journalists, artists, academics and scientists. I strongly believe that we hold freedom of the press and other media, freedom of artistic creativity, academic freedom and freedom of scientific research in trust for everyone

For me freedom of expression means that decisions about what to publish, for example, rest squarely on the shoulders of the journalists. As soon as that decision is located in an external agency, like a statutory Media Appeals Tribunal, the right guaranteed by the Constitution of the country is curtailed.

The tribunal would have to prescribe what good journalism is and then punish those who do not live up to that prescription.

The limitations to freedom of expression are spelled out in the same section of the Constitution: We may not be propagandists for war, incite imminent violence or advocate hatred based on race, ethnicity, gender or religion and that constitutes incitement to cause harm.

There are, of course, the usual common law and legislative limitations that boil down to allowing me freedom of expression only to the extent that I don’t unlawfully violate the rights of another person. For example, if I defame you in a speech, you can sue me in court or if I trespass on your property, you can call the police to arrest me.

Irony is that some people will swear that they believe in freedom of expression, but in the same breath, they will shout that we should jail errant journalists and ban them and their publications. This tells me that our democracy is only skin-deep as we regress easily to what the Nationalist Party represented.

And that reminds me of the analysis offered by Frantz Fanon years ago: ‘The settler’s world is a hostile world, which spurns the native, but at the same time it is a world of which he is envious. ‘

‘We have seen that the native never ceases to dream of putting himself in the place of the settler – not of becoming the settler, but of substituting himself for the settler.’

Some of the sentiments and even the actual phrases used in the current debate about self-regulation could easily be direct quotes from the rhetoric of the Nationalist Party in the 1960s, 1970s and the 1980s.

The press has acknowledged the generosity of our society and voluntarily adopted the Press Code ‘to promote and to develop excellence in journalistic practice and ethics’. Around 700 publications – ranging from grassroots, to community to commercial – have taken away the need for external control by subscribing to the Code. It is a decision they took voluntarily and that is thus in the line with the Bill of Rights.

Ladies and gentlemen, the Norwegian journalism teacher, Helge Rønning, says ethics is about how we should live our lives: ‘(It) focuses on how one decides what is right and wrong, fair or unfair, caring or uncaring, good or bad, responsible or irresponsible.’

Ethics is crucial in the decision-making in journalism just as much as it is crucial in business and in all our daily lives. A journalist decides what story to cover, who to interview for the story, what questions to ask, what words and pictures to use to tell the story and the editors have to decide where to place the story and what headlines to put over it. It is a day-long process of decision-making

At each fork in the road the journalist has to ask: What here is right and wrong, fair or unfair, caring or uncaring, good or bad, responsible or irresponsible?

I’m sure the graduands here will recognise the similarities between the life of journalism and that of commerce. As with all decision-making, journalism starts with the question: Why are we doing this?

The Code says: ‘The primary purpose of gathering and distributing news and opinion is to serve society by informing citizens and enabling them to make informed judgments on the issues of the time.’

It also states: ‘The freedom of the press allows for an independent scrutiny to bear on the forces that shape society.’

I believe it is vital that journalists ask the question about why they are doing a story because it reconnects them to their values as individuals and to the values of the publication they work for.

I have found that great journalism around the world is motivated by much, much more than the pay cheque at the end of the month.

The Code then goes on to define good journalism: truthful, accurate, fair, in context, balanced and does not intentionally or negligently depart from the facts by distortion, exaggeration, misrepresentation, or material omissions. Almost all the newspapers and magazines in our country have committed themselves to following this Code. Some still fall short.

I sit in my office and receive complaints from the readers about the performance of their newspapers or magazines. From this perspective, the negative looms large and it is quite easy to tell myself that journalism is going to the dogs. And it is probably worse if you happen to be the victim of bad journalism. It might be all you will remember about journalism and journalists.

Last year, for example, our office got 213 complaints. For me, one complaint is one too many. Bombarded by these complaints, however, I often have to sit back and give myself some distance. At these moments, I have to acknowledge that journalists churn out millions of words every day and 213 complaints in one year is a drop in the ocean. I have to concede that by and large, journalists are living up to the promises of the Code: ‘To serve society by informing citizens … ‘

Almost all that you and I know about our country, its people and the world, we picked up from our newspapers, magazines, radio, television and online.

As you graduate today and stride into the world of commerce, you will be using media to communicate and you will in turn be receiving information, ideas and opinions from them. They are not perfect but you can help to push them to be even better by demanding that they live up to their commitments in the Press Code.

And as you start your life in business, in every decision you make, you too have a chance to ask: Why am I doing this? What is my real motive? How does it fit into my values and the values of my corporation? In what way are my values different from those of the erstwhile oppressors in this country, or have I merely taken those values and put them on as my own?

How do my actions measure up against the national agenda accepted by all South Africans in December 1996 and expressed in the preamble to our country’s Constitution:

- Heal the divisions of the past and establish a society based on democratic values, social justice and fundamental human rights

- Lay the foundations for a democratic and open society in which government is based on the will of the people and every citizen is equally protected by law

- Improve the quality of life of all citizens and free the potential of each person, and

- Build a united and democratic South Africa able to take its rightful place as a sovereign state in the family of nations

Congratulations to all the graduands. The wide horizon beckons …