In the crosshairs: journalists fighting for justice in the Middle East

Devin Windelspecht

When Rana Sabbagh was a young girl in Jordan, her German mother introduced her to the idea of Gerechtigkeit, which translates roughly to ‘justice’ or ‘fairness’. Sabbagh’s career as an investigative journalist has revolved around this ideal: that justice, accountability and the rule of law matter — in the Middle East especially so, as governments and powerful actors regularly enjoy impunity for corruption, human rights abuses and violations of international law.

In 2005, Sabbagh, ICFJ’s 2024 Knight Trailblazer Award winner, co-founded the Arab Reporters for Investigative Journalism (ARIJ) to train investigative journalists in the Middle East. During her 15 years as executive director, she mentored an entire generation of Arab reporters, many of whom have gone on to uncover corruption and abuses of power in Egypt, Syria, Gaza, Lebanon and beyond.

Today, Sabbagh continues to drive hard-hitting investigations as senior editor for the MENA region at the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP), where she’s reported on state-sponsored drug trafficking, government corruption, sanctions evasion and more. Her investigations have led to international sanctions, arrest warrants and criminal investigations, among other impacts.

Sabbagh’s reporting naturally has put her in the crosshairs of powerful actors. She has had her phones tapped, and attacks on her have caused her to suffer burnout from psychological stress, not least when authorities have pressured her to choose between her country and her role as a journalist. But she has not stopped bringing to light the crimes those in power want hidden.

‘I cannot travel to at least eight countries [in the MENA region],’ Sabbagh said. ‘But I don’t really care about [being able to travel to] these countries. I care that I’m able to tell the story and I’m able to expose corruption, and hopefully do some little change with the results of the work that we do’

Sabbagh started her career in 1985 as a journalist at the English-language Jordan Times. Two years later, she joined Reuters as the agency’s deputy bureau chief in Jordan.

On her third day in the role, she received a tip about the presence of anti-government riots in the country’s south, at a time when Jordan was under martial law and information tightly controlled. Her first big scoop — which forced the King of Jordan to cut short a trip from Washington, D.C. to return home — also exposed her to the risks inherent to reporting in the region.

‘I was in the office; I thought every time the door knocked, they were coming to arrest me,’ she said.

She reported on a slew of major stories in the Middle East while at Reuters, including the Israel-Jordan peace process, the 1991 Gulf War and internal conflicts in Jordan, all while confronting sexism and her colleagues’ underestimation of her abilities.

‘There were no women covering riots, they were all men with cameras. They used to look at me like, “What’s this idiot girl doing here?”,’ she recalled. ‘They always looked down on me because I’m half-foreign. I’m blonde, I’m a girl. Nobody [like me] was working these tough beats. But there I was sitting on the pavement waiting for Yasser Arafat to appear at four in the morning because that’s when he gave us the interviews.’

Sabbagh returned to the Jordan Times in 1999 as the paper’s Chief Editor, the first woman in the Levant region to lead a political newspaper. She turned what had been a mouthpiece for the government into a truly independent paper.

‘I grew the local content, and everyone started calling it an opposition paper,’ Sabbagh said. ‘I’m not really an opposition person, I’m just a very professional person. I Reuter-ised it.’

This independence would come at a cost. After Sabbagh sent a reporter to investigate allegations of torture carried out by Jordanian authorities in response to riots in the country’s south, she published an op-ed calling for investigations into the use of torture at police stations.

After resisting government pressure to adopt the official line refuting that a protester’s death had resulted from torture, she was confronted by the paper’s chairman and told that she would no longer be Chief Editor. Sabbagh left the Jordan Times immediately.

‘The fact that I used the word “torture” in a in a newspaper that was 60% owned by the government made them really flip,’ she said. ‘I got dropped in a second’

It wouldn’t be the last time Sabbagh would be forced to choose between the government’s insistence on loyalty to her country and her independence as a journalist.

Being removed from one of the region’s top English-language papers could have been a career-ender. Sabbagh instead used it as an opportunity to chart a new path for independent journalism in the Middle East. In 2005, she founded ARIJ, the region’s first network of investigative journalists.

Introducing investigative reporting to the region was no easy task. At the time, knowledge on how to conduct investigations was nearly non-existent in the Arab region, Sabbagh said: ‘When I started at ARIJ, honestly, nobody had a clue what investigative journalism was. Even myself; I didn’t have a clue. But I was a very good reporter, trained at Reuters. I knew how to develop sources, how to protect sources, how to dig. These are the basics of investigative [reporting].’

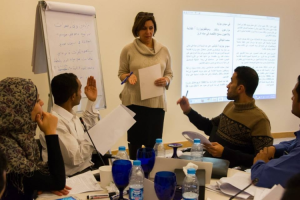

Recognising the dire need for training, ARIJ held six workshops per year for aspiring investigative journalists to develop their stories. Participants would go on to carry out roughly 600 in-depth investigations over the course of Sabbagh’s directorship. With UNESCO funding, ARIJ also created an investigative reporting training manual that is still currently taught in universities worldwide today.

By the end of Sabbagh’s 15-year tenure leading ARIJ, the organisation had trained more than 4 000 journalists, including award-winning reporters in their own right from Gaza, Lebanon and Egypt, among others.

‘ARIJ did something amazing for the Middle East. In the future, when they talk about investigative journalism, ARIJ is going to be named as the pioneer that introduced this genre of journalism [to the region],’ Sabbagh said.

She stepped down from ARIJ in 2019 to make way for new leadership, but she continued investigating corruption and human rights abuses in the region. In 2020, she became the OCCRP’s senior editor for the MENA region where she revealed the Syrian regime’s involvement in the trafficking of the powerful amphetamine, Captagon, broke the story on how the son of Lebanon’s central bank governor sent millions of dollars abroad during the country’s economic crisis, and detailed how an Iraqi bank channelled money to alleged funders of terrorism, among other stories.

Sabbagh’s investigations have had real impact, spurring calls for sanctions reform in the EU, for instance, and contributing to the passage of a bill in the U.S. aimed at dismantling criminal organisations involved in narco trafficking in Syria.

‘Sometimes [impact is] slow, sometimes it’s fast, and sometimes it takes time and sometimes you build on it,’ she said. ‘I’m very excited to say that good reporting always creates impact, even if it’s a good feature or a good in-depth piece. It doesn’t have to be an investigation. It’s the quality of journalism that matters.’

Sabbagh is clear-eyed about the risks that come with the rewards of investigative journalism, however. She’s been detained multiple times by authorities, and had her phones infected with Pegasus spyware at a time when she was investigating high-level Jordanian officials.

The new era of technology means new challenges for investigative journalists, Sabbagh warned. ‘There are wars in the Middle East, but the hostility hasn’t changed [from past years]. What changed is cyber security and cyber safety. They’ve become really smart, whether it’s state agents or it’s the mafias. It’s become very easy to find encryption. It’s become very easy to find eavesdropping equipment,’ she said.

Her advice to investigative journalists? Know what you’re getting into, and be prepared to acknowledge if it’s not right for you. ‘It’s not easy, but it’s passion. You have to be a person who believes in justice and accountability and rule of law and punishing the bad guys that use taxpayers’ money, and use their positions to oppress others and to steal the wealth of people,’ she said. ‘It’s tough. It’s not easy. And if you can’t make it, don’t go into it’

Nevertheless, the need for impactful investigative journalism is more important than ever in the region.

The Israel-Hamas war, for instance, will present opportunities to investigate the future presence of security companies in Gaza, contacts for offshore gas drilling and war profiteers who make money off of Palestinians trying to leave Gaza, among other avenues of investigation, she said: ‘There’s going to be a lot of corruption, and this is where we will need investigative journalism.’

In accepting the Knight Trailblazer Award, Sabbagh credits the many colleagues she has worked alongside. ‘I give this gift to everybody that I worked with in my 40 years, that’s been great to me and believed in what I wanted to do,’ she said. ‘Whether it’s my staff, whether it’s people that trained me, whether it’s people I trained, we all ended up supporting each other. And without the support, [ARIJ] would have never taken off.’

Sabbagh is determined that investigative journalism continues speaking truth to power in the Middle East — especially when doing so is challenging. ‘I hear today that they’re saying, “Society doesn’t want to hear anything about investigative [journalism]”.

‘This is bullshit. Society is very tough. Economic situations are very tough. Political situations are very tough,’ she said. ‘I’m asking myself, when was it easy? It was never easy.’

- This article was first published here